How to Frame Problems With the TOSCA Framework Like Top Strategy Consultants

A practical guide on defining problems well so that solving them becomes much easier.

How good are you at problem-solving? And why does it matter?

Problem-solving is one of the most underestimated skills. It’s the 2nd most important competency, according to the Harvard Business Review survey among 300,000 Managers.

IQ explains only 20% of the variance in problem-solving effectiveness. These surveys show that problem-solving skills will be more important in the future. In work and life.

What do I mean by Problem-Solving Skills?

I refer to the ability to apply systematic approaches in any given field to generate good solutions.

When I was in university, luckily, I had a complete course about systematic problem-solving taught by a senior partner at McKinsey Management Consulting in university.

It was gold.

I worked as an engineer, entrepreneur, consultant, and manager. Problem-solving has become my passion. I practice everywhere.

One of the keys is defining the problem well. That’s what I will explain in this article.

If I can’t state the problem in a clear and precise way, I don’t understand it properly

So how does it work? How do I define a problem? And how do I know I’m ready to start working on the solution?

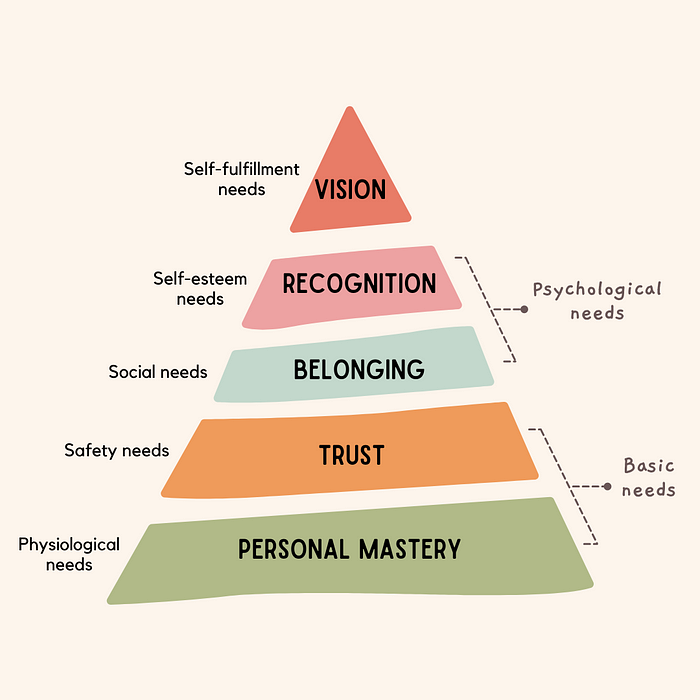

The answer is the TOSCA Framework used by strategy consultants to define problems: Trouble, Owner, Success, Constraints, and Actors.

The Trouble

The trouble is not the real problem. It’s the symptom — a gap between the status quo and a desired future state. It triggers our journey of problem-solving.

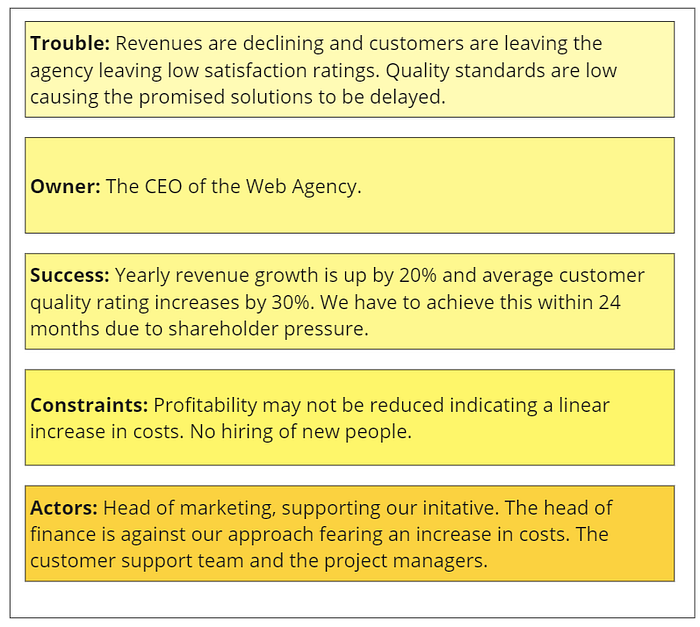

For example, I was advising the owner of a web agency. Their revenues were stagnating, but they aspired for a 20% growth per year.

That discrepancy is the trouble and has to be defined clearly.

To properly define the problem, we have to resist the urge to solve it too quickly.

Asking open-ended questions

- What do you want to achieve?

- What have you tried?

- Why did it not work?

- What else?

Being specific

Don’t accept vague ideas or descriptions. For example: “We have to be more customer-centric” is not a problem.

But “10% of our customers leave us after one year” is a trouble I can address.

Not jumping to conclusions

For instance, stating, “Customers are leaving us because our service isn’t good,” is only an interpretation.

On the other hand, “5 out of our last 10 clients filed complaints” provides a tangible symptom that I can work with.

Asking “ Why” to get to the root causes

Why did the customers complain?

Because we took too long to deliver our solution. 4 weeks instead of 2.

Why?

Because we had too many quality issues.

Interesting!

So, one trouble seems to be related to quality. I can now ask: How many issues? How long does it take to resolve them? What is the aspiration?

This way, I can work towards the real issues.

The Owner

Whose problem is it? Sometimes it’s obvious, but not always. It can be a person or a group of people.

I need somebody to ask What do you want?

In some cases, asking who the owner of the problem is leads to an interesting discussion.

For example, let’s assume I work in the music industry, and piracy is a problem for the entire industry. But who is the industry? Is it the RIAA or the management of music labels?

In the above example of the web agency, it’s the CEO of the company that I’m advising.

The Success

I have to know the goal of the problem-solving. That’s how I will later measure the success. But how do I define success?

By asking the right questions: Imagine we’re in the future, and this problem-solving effort has been very successful. What’s the date, and what is different? What do you see? And what else?

Let’s pick up our example. I’m talking to the agency’s CEO.

I say: We are in the future, and we have achieved our dream outcome of this project. What is the date?

-I think it’s 12 months later. It’s not an easy issue to solve.

-What do you see? What’s different?

-Our revenues are growing again because our customers are not leaving us anymore. Instead, they keep coming back and even recommending us.

-How will you know? How do you measure it?

-Instead of complaining, they give us 5-star Google ratings.

Interesting. Customer feedback is one success criterion, as well as revenue.

The Constraints

I now have a grasp of the problem I’m solving. But there are always some limitations to what I can do.

Asking: What are the constraints? Don’t get me far.

It’s better to check for specific limits in 3 dimensions:

Constraints on success criteria

There are typically several conflicting goals.

In the example, I try to increase revenue. But I cannot do that at all costs. I also have to ensure customer satisfaction, quality, and profitability.

Constraints on the solution

What type of solutions are off-limit due to our resources or capabilities?

For example, as a digital agency, we don’t have the skills to offer detailed consulting to the clients.

Hiring new people is also off the table as the budget is too small.

Constraints on problem-solving process

These involve limits on who I can talk to, how much time I can spend finding the solution, or confidentiality agreements.

For example, I may not be allowed to question the customers of the agency directly.

Defining these constraints will save me painful iterations later in the process.

The Actors

There are always more people to be considered.

Actors are stakeholders whose objectives I have to understand. They usually deviate from the owner’s goals.

They can support or resist my problem-solving efforts.

I must understand what they want since they all have varying degrees of influence.

The best thing to do is Power Dynamics Mapping. This will display my supporters and resistors and how much influence they have.

The blue boxes on the map display the actors’ initials, and the lines indicate strong relationships.

I cluster them according to their influence (power) and their interest to support me. This will show me where to focus my efforts.

I explain the how-to’s and details of Power Dynamics Mapping here.

For example, the head of marketing may be supportive because she also wants to improve customer satisfaction.

The head of finance might oppose me because he is focused on cost-cutting and my problem-solving attempt is expansive.

The Core Problem Statement

After following the TOSCA steps to grasp the problem, I summarize my findings:

Now, I write the core question I’ll answer.

First, I decide between a closed and an open question. This has a large impact on the solution space that I’ll be working in.

Look for an example at the following two questions:

- How can we grow our revenue?

- Should we hire quality consultants to improve customer satisfaction?

The first one is open and gives me a lot of freedom to come up with ideas. The second is narrow and doesn’t leave much room for ideation.

As a rule of thumb, if I’m tackling a big problem and am still early in the process, a broad question scope will be better.

Secondly, I can use the following checklist to write my core question:

- Does the question address the trouble?

- Is the question written from the point of view of the owner?

- Will solving this question lead to the success you defined?

- Does the question take into account the constraints?

- Is the question scoped in a way that makes it clear that there are different actors?

This could be the core question of the web agency in our example:

How can we grow our revenue by 20% while increasing customer satisfaction by 30% without hiring new employees and keeping our current profitability within two years?

Final Thoughts

There isn’t the right way to define a problem. But there are many wrong ones.

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.” — Albert Einstein

Using TOSCA gives me a frame of the problem. It helps me take into consideration all angles:

- What’s the trouble that’s triggering our quest?

- Who is the owner?

- What is the success that we try to achieve?

- What constraints are there?

- What actors do we have to consider?

By distilling the findings into the core question, I position myself to solve the right problem effectively.

Keep in mind that defining the problem is an iterative process. I always:

- Emphasize with stakeholders

- Do interviews and immerse myself

- Integrate the views of several actors

- Reassess the core question at times

A well-defined problem is half-solved