50% of What You Learn at Age 20 May be Outdated by 30. Here’s a Plan to Stay Ahead.

#1. Living = Learning

Centuries ago, you could survive by learning everything you needed to know in your youth.

A few years of good education and you were ready for practically anything.

Not anymore.

In the fall of 1971, the first ever email was sent by a computer scientist.

Regular people who lived at that time didn’t have to learn what an email was or how to send one.

Fast-forward thirty years later, email becomes available on the blackberry.

Today, there are about 4.48 billion email users worldwide.

Things didn’t always move so fast, though.

Innovation is a self-sustaining cycle, and the time from the generation of a creative idea and its diffusion through society has been shortened dramatically.

And it keeps getting even shorter and shorter.

This means there is a constant barrage of new information, technology, and tools that are changing the world works.

“In a world in which the half-life of many facts (and skills) may be ten years or less, half of what a person has acquired at the age of twenty may be obsolete by the time that person is thirty.” — Malcolm Knowles

If this is true, then what’s the point of learning?

Why should we learn things that are going to become outdated in a decade anyway?

The answer is pretty obvious: there are no other options.

To make a living today, you need to be ready to learn new things every day, like your life depended on it.

No two ways about it.

You must begin learning how to learn on your own terms.

In this article, I’m going to talk about what it looks like to be proactive about your learning and self-development

Consider it a mini-guide for living in this fast-paced age.

1. Living = Learning

You need to equate living to learning.

Be intentional

Last week, I was ‘forced’ to have lunch with a visiting professor and another colleague at my university.

As an introvert, such interactions have always been extremely uncomfortable for me.

My colleague did most of the talking, and I listened as she asked questions about the job market and career prospects in our field.

The professor’s answers were succinct and brutally honest.

He gave two critical lessons he learned from job-searching.

Those were some solid lessons that could have easily found their way into someone’s best-selling autobiography.

To get that information, I would’ve had to buy a book and then use hours to comb through it diligently for those tips.

Have you wondered how much you could learn if you took notes from your everyday conversations?

I love textbooks, Christian literature, and good non-fiction books on my subjects of interest.

But it’s becoming progressively impossible to read all the books you need to read to stay informed.

So, to get ahead, you must learn to guide every interaction or conversation into a learning experience.

Be intentional.

Whenever you have an opportunity to meet people, find out what they’re good at and what field they’ve had training in.

Then ask them three questions that they are capable of answering because of their experiences.

Feel free to borrow these questions if nothing comes readily to mind during your conversations:

- What are some misconceptions about your field that you find yourself having to correct a lot?

- If I wanted to learn one thing in your field, what would it be? What’s the best way to learn it on my own?

- What’s a skill/software/tool that is often overlooked but is very crucial in your industry/field?

- In your opinion, what’s the most exciting development/technology emerging your field today?

If you already know something small about their industry, ask them to explain a specific concept to you like a layperson.

If you come across something particularly relevant, make a quick note on your phone and revisit it.

You will soon begin to find tools or skills that are broadly applicable across different fields.

You can start learning the ones that pique your interest on your own.

Be a copycat (ethically, of course)

My biggest challenge when I moved to a different country was the realization that silence during a conversation was generally abhorred.

People over here like to keep conversations going. It puts me under a lot of pressure to find responses or questions of my own.

So, I just started listening more closely to the people in my lab who were particularly good at these kinds of conversations.

When we were in a group, I would allow myself to consciously learn the way they kept discussions going, with no awkward breaks.

Even with the online videos I would watch during my downtime, I listened closely and absorbed.

And then I started mirroring those conversation patterns and gestures.

I borrowed words and phrases, adding my own twist.

It has helped immensely.

It takes too much time and effort to try to reinvent the wheel.

It’s unnecessary, especially when there are people around you who do something decently well.

Being a good communicator is crucial.

It keeps getting even more important as the world collapses into a global village.

I’m learning this soft skill from my everyday observations.

I read books as a supplement, but people-watching makes learning 10X faster.

Then, it allows me to use my focused learning periods for more technical skills.

Be flexible

Some people picked up skills in the late 90’s and still choose to clutch onto them no matter what.

I’ve met a few who loathe AI because it’s just going to make us lazy or take our jobs away.

But honestly, there are things you just can’t keep fighting forever.

Lean into it fast, and not when it’s too late.

When you hear there’s a new trend, tool, or technology, prick up your ears.

Ask questions and find out if it’s within your space.

If your research shows that it’s relevant, find ways of adapting your existing workflows to include it.

2. Read proactively

How do you read textbooks, reference books, and manuals?

How about non-fiction?

Here’s the way I used to do it: I’d start at page 1 and read all the way to the end, taking notes.

Not too bad, right?

Well, this method works for certain types of literature that follow a sequential order, like fiction.

But technically, it’s just passive or reactive reading.

You’re taking what the teacher (the author) has for you and swallowing it whole.

It’s just like school where you sit at the feet of your experienced teacher and absorb till your brain expands.

It works. Well, hopefully.

But it’s not as effective as being a proactive reader.

Proactive reading is tailoring your reading to your learning needs at a particular point in your life.

Imagine you’ve bought or acquired a new book about online writing.

Before getting the book, you would’ve read the publisher’s summary/purpose of the book.

Instead of reading from start to finish, do this:

Step 1: Flip to the back of the book or wherever the author’s profile or credentials are detailed out.

If the book doesn’t have that information, Google the author’s name and read about them.

Be curious about what their portfolio looks like.

What are they an authority in?

What are they qualified to teach you based on their credentials?

Step 2: Read the introduction, foreword, or preface of the book.

This is the author’s or someone else’s description of the book.

It’s like the author’s manifesto of what they hope to deliver.

Take note of who their target audience is and make sure that you’re likely to benefit from reading the book.

3. Based on the introduction and the author’s profile, make a list of 3 things you hope to learn from the book.

Write down a few questions you became curious about during your preliminary examination of your book.

Specify what type of information you’re looking to get.

One example, using the online writing book:

- I want to learn how to write engaging headlines.

- I want to learn more about consistency and perseverance when writing online without an audience.

- I want to learn how to make money writing online.

4. With your list ready, head over to the index or table of contents and find the section that answers your first question.

Write notes.

Were you satisfied by the author’s answers or do you need more information?

Did the new information make you curious about something else?

Take some time to think about the author’s answers and how practicable they are in your circumstance.

Then rinse and repeat till you have answers to all your questions.

If there’s background in a different part of the book, flip over there and only read the information you need.

Do this for any book as often as you need to.

It helps you read for you.

You’re not passively absorbing information that the author thinks you should know.

You become the boss of your learning and you save some time as an added bonus.

3. Be a self-directed learner.

In a world where you’re challenging yourself to constantly learn, two things are key: maximizing time and being conscious of your learning goals.

You want to be sure you’re doing as much as you can, with whatever amount of time you can create.

Sit yourself down and identify topics, themes, or fields that you want to master.

It can get overwhelming when you look at all the things you want to learn.

Sometimes, indecision even cripples you and keeps you from starting.

Or maybe you’re a serial quitter who always starts to learn a skill and stops halfway.

These articles will help you figure out what you can focus on learning and how to overcome learning obstacles:

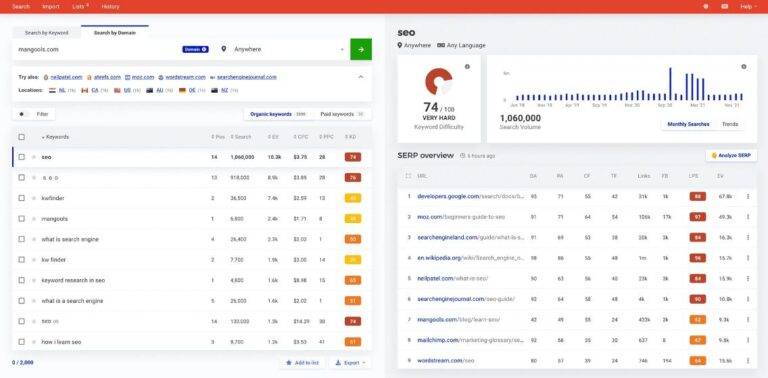

3 Simple Questions to Figure Out Your Learning Path

Learn a new skill that resonates with your soul.

5 Sneaky Obstacles Stopping You From Learning New Skills

You are one skill away from a breakthrough. Only problem is you’re too busy.

Once you’ve figured out a skill you want to learn and master, decide on how much time you can commit each day to focused learning.

Find some time to create a list of specific learning objectives and a personalized curriculum.

You must have practical time points and rubrics for assessment.

These planning systems help to keep you in check and on track towards proficiency in a skill.

While learning is definitely an infinite process, you should always strive to achieve some level of mastery.

Work to get to a point where it won’t always feel like a grueling upward trajectory.

To be able to make sure you’re getting there gradually, you need to have objective measures for assessing yourself.

This is where it gets a little tricky.

Who gives you a grade when you’re directing your own learning?

You evaluate yourself.

For self-directed learning, that’s non-negotiable.

Set periods for regular assessment: Weekly, fortnightly, monthly…

During these times, be hard on yourself and lay out the truth about your progress.

How much did you learn over the period?

How did you apply the new knowledge practically?

How ready are you to teach someone else what you’ve learned?

With deliberate evaluation on your journey to master new skills, you decrease your chances of slacking off and wasting your time.

Finally, make plans to teach other what you’ve learned — either face-to-face or by writing about it online.

This is how you allow yourself to actively engage with the material and field questions about it.

TL;DR

Learning in today’s world is like riding a roller-coaster of change.

How do you stay ahead?

- Turn everyday interactions into learning experiences. Be genuinely curious about the people you meet and ask smart questions.

- Absorb soft skills by observing those around you.

- When reading a book: flip to the end, read the author’s bio, and dig through the text with a purpose.

- Self-directed learning is not just a luxury, it’s a must. Plan and set objectives, evaluate yourself, and share what you learn with others.

If you want to outpace the diminishing half-life of facts and skills, master your own learning and seize every opportunity.🚀

References

- Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers.

2. Toffler, A. (1970). Future shock, 1970. Sydney. Pan.